The American Revolutionary War is a source of celebration for all Americans. The claims of the Declaration of Independence are taken for granted, and it is considered to have been a just war. However, under scrutiny, this war cannot be considered just.

John D. Roche writes,

Historically, Christian thinkers have held that biblical passages such as Romans 13 clearly prohibit rebellion. Although a few Catholic writers such as John of Salisbury argued that tyrannicide may be justified in extreme circumstances, prior to the Protestant Reformation the vast majority of Christian thinkers rejected its legitimacy. Early Protestant leaders, including Martin Luther and John Calvin, initially accepted this view, but by most accounts they eventually embraced the position that inferior magistrates may actively resist tyrants. Within a generation, Calvinist thinkers such as John Ponet, Christopher Goodman, George Buchannan, and Samuel Rutherford had embraced this position. That Calvinists developed such a robust resistance ideology is particularly important in the American context as this tradition was, according to Sydney Ahlstrom, “the religious heritage of three-fourths of the American people in 1776.”

But it was not only Calvinists who argued that tyrants may be resisted. Particularly important in the American context is John Locke’s Second Treatise on Civil Government (1689). Locke was likely influenced by earlier Calvinist thinkers, but he secularized and helped popularize the idea that the people themselves could justly overthrow tyrannical governments. As well, patriot colonists were influenced by the Whig political ideology which developed between the turn of the seventeenth and the early eighteenth century.[1]

It was this Protestant perversion of just-war theory which fermented in Britain and adopted by Americans that allowed the latter to justify what they claimed was resistance of tyranny. Protestant clergy in the colonies preached that resisting tyranny was a duty, one such figure being the Boston Congregationalist minister Jonathan Mayhew who stated that “Common tyrants, and public oppressors, are not entitled to obedience from their subjects, by virtue of anything here laid down by the inspired apostle.”[2] There were other influential pastors like

the Presbyterian Abraham Keteltas. Keteltas preached a sermon entitled “God Arising and Pleading His People’s Cause” in 1777 during which he expounded upon the religious dynamics of the American struggle, arguing that “the cause of this American continent, against the measure of cruel, bloody, and vindictive ministry,” was “the cause of God” and that, since the colonies were God’s chosen people, Britain’s war against the colonies was “unjust and unwarrantable.”[3]

For American patriots, “the interrelated issues of taxation, representation, and Parliamentary sovereignty formed the central crux of the imperial debate and justification for their rebellion.”[4] But simply put, the tax situation did not justify armed rebellion.

When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, the colonies were only paying £1,800 annually. Although Parliament did seek a thirtyfold increase, £60,000 annually with the Stamp Act, this amount would only cover seventeen percent of the £350,000 required to keep ten thousand regulars in the colonies. More importantly, the colonists’ tax burden paled in comparison to that of those living in England. Following the Seven Years’ War, Britons in the home islands paid an average of twenty-five shillings annually versus the colonists’ six pence of imperial taxes, which translates to fifty times the colonists’ tax rate.[5]

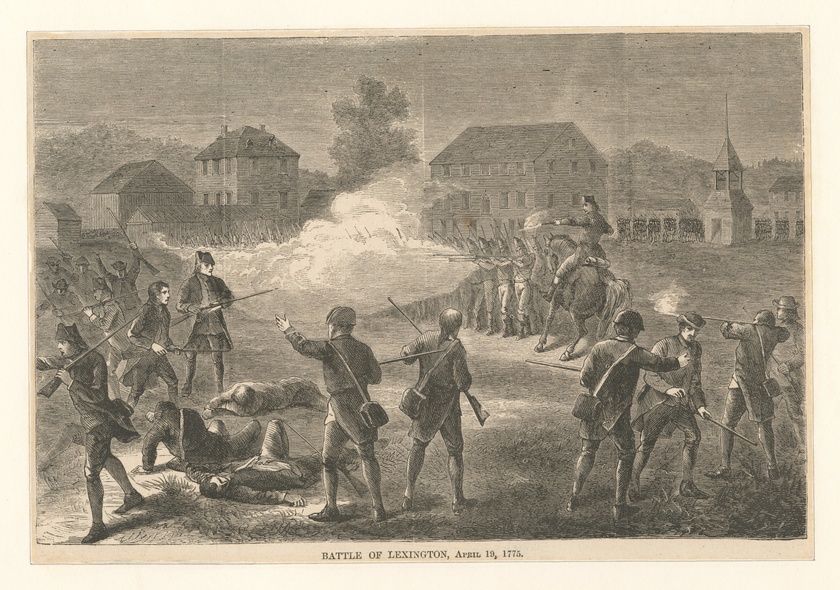

Although the Declaration of Independence claimed that “[King George] has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us,”[6] it was actually Americans who escalated violence from Lexington that led to complete warfare. British troops marched to Concord in an effort to prevent armed conflict by seizing weapons thought to be there. However, the Lexington militiamen refused to be disarmed since they insisted they had a right to self-defense. When these two forces met, British Major John Pitcairn ordered the militiamen to disperse, which they refused. Pitcairn never gave the order to his men to fire, but the shooting did commence, although we don’t know which side fired first. This outbreak of hostilities resulted in eight dead colonists and nine others wounded, while on the British side the only casualty was a soldier with a bullet through his thigh.

When the British finally made their way to Concord, they destroyed all the war material they saw. They also set fire to the town’s liberty pole, a fire which then spread to the courthouse nearby, which is when things got out of control. As Roche writes,

the town’s militiamen who had been watching from above the North Bridge mistakenly believed the British were burning the entire town. This prompted them to attack, and the New England militiamen harried the British troops all the way back to Boston. When the British had finished running their gauntlet, 73 were dead, 174 had been wounded, and another 26 were missing. On the American side, only 49 had died, 39 were wounded, and 4 were missing. The colonists followed up this assault by laying siege to the city of Boston with an Army of Observation. The patriots further escalated the conflict when the Second Continental Congress adopted the Army of Observation as the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, and made George Washington its commander. By this action, the Congress transformed a regional rebellion into a continent-wide civil war. Four days later, the New England troops enticed the British to attack them by fortifying Breed’s Hill. The final aggressive act the colonists made prior to the Declaration of Independence was the invasion of Canada. The Americans hoped to wage a war of liberation and make Canada the Fourteenth Colony. At a minimum, it seems reasonable to classify the patriots’ actions as something more than mere “self-defense.”[7]

Roche concluded:

By any measure, the War of Independence was not a war of last resort. The British were still willing to make compromises through the summer of 1776. Parliament proposed the Conciliatory Resolution in February 1775, which offered to allow the colonies to tax themselves as long as they contributed “their proportion to the common defence.” The Continental Congress rejected this offer. When Admiral Lord Richard Howe and General William Howe arrived in New York City at the head of thirty-two thousand troops in July of 1776, they came not only as military commanders but also as peace commissioners. They were authorized to settle the issue of taxation under the terms of the Conciliatory Resolution, as well as grant pardons and remove trade restrictions. Unfortunately for Lord Howe, the Americans declared independence eight days before he arrived.[8]

Because of the colonists’ drive for war, tens of thousands perished in an unjust war:

Throughout the course of the war, an estimated 6,800 Americans were killed in action, 6,100 wounded, and upwards of 20,000 were taken prisoner. Historians believe that at least an additional 17,000 deaths were the result of disease, including about 8,000–12,000 who died while prisoners of war.

Unreliable imperial data places the total casualties for British regulars fighting in the Revolutionary War around 24,000 men. This total number includes battlefield deaths and injuries, deaths from disease, men taken prisoner, and those who remained missing.

Approximately 1,200 Hessian soldiers were killed, 6,354 died of disease, and another 5,500 deserted and settled in America afterward.[9]

[1] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 51). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[2] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 53). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[3] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 53). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[4] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 58). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[5] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 59). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[6] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 60). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[7] America and the Just War Tradition (pp. 60-61). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

[8] America and the Just War Tradition (p. 62). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.