JFK had no intention of ending the war in Vietnam, despite claims of his associates and pointing to National Security Action Memorandum 263. His plan of U.S. withdrawal was always contingent upon victory; if there was no faith in the South Vietnamese government, American troops were there to stay. South Vietnam had to be in a position where they were guaranteed to defeat the Northern military forces for U.S. troops to withdraw from the conflict.

During John’s presidency, he and Robert Kennedy continuously reiterated the desire to see the war through until victory against North Vietnam was achieved.

In 1956, while still a Senator, he said:

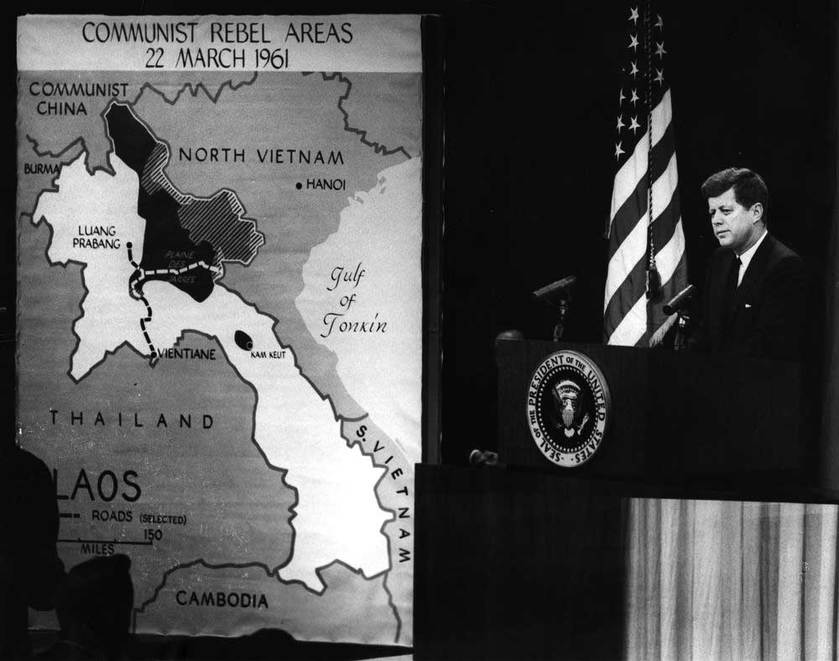

Vietnam represents the cornerstone of the Free World in Southeast Asia, the Keystone to the arch, the finger in the dike. Burma, Thailand, India, Japan, the Philippines and, obviously, Laos and Cambodia are among those whose security would be threatened if the red tide of Communism overflowed into Vietnam... Moreover, the independence of Free Vietnam is crucial to the free world in fields other than the military. Her economy is essential to the economy of all of Southeast Asia; and her political liberty is an inspiration to those seeking to obtain or maintain their liberty in all parts of Asia—and indeed the world. The fundamental tenets of this nation’s foreign policy, in short, depend in considerable measure upon a strong and free Vietnamese nation.[1]

On July 17, 1963, he stated: “for us to withdraw from that effort would mean a collapse not only of South Viet-Nam, but Southeast Asia. So we are going to stay there.”[2] Then in an interview with Walter Cronkite on September 2, he said: “I don’t agree with those who say we should withdraw. That would be a great mistake... It doesn’t do us any good to say, ‘Well, why don’t we all just go home and leave the world to those who are our enemies’... We are going to meet our responsibility.”[3]